by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

Distinguishing what’s happening in the market and the direction of important market metrics – the signal – from garbled, inconsistent, and mostly useless data – the noise – is extremely challenging today. Information is contradictory and transient making data and critical events more confusing and indistinguishable. Unusual circumstances brought about by the pandemic, subsequent supply chain interruptions, inconsistent production and demand, and unclear economic forecasts combined for almost unprecedented uncertainty and unpredictability.

Typically, near-term predictions are reasonable and reliable because we have immediately available and fairly accurate data making short-term predictions reasonably accurate. In other words, we can estimate what will happen because we have a good idea what just happened. But this is not the case today. Predictions based on the near-term past are more muddled now than ever. While we used to be able to say we can see a trend, whether that’s inflation, economic growth, or some other important metric, too much volatility, irrelevance, and lack of applicability (after all, who is going to project from a base that includes a pandemic impacting global supply chains and production?), we really can’t reasonably rely on any of that data to try to find a trend or connect the dots generating a near-term forecast with any meaningful depth of data and understanding

More intense volatility occurring more often will be characteristic of this market from now on. An investment strategy must withstand and profit from this. The only clear signal from the market is that there is far too much noise and not enough of a clear signal. Without clarity, determining an investment strategy is flying blind with no instruments.

Core holdings combined with an ability to withstand and profit from volatility and unpredictability are essential for investors today.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

Assume nothing, new models and analytical tools, coupled with constant revision, questioning everything, reassessing, and re-analyzing, are essential to success in today’s markets. Often, and we are seeing that in today’s market, relying on bad assumptions, dogma, or prior belief can be disastrous.

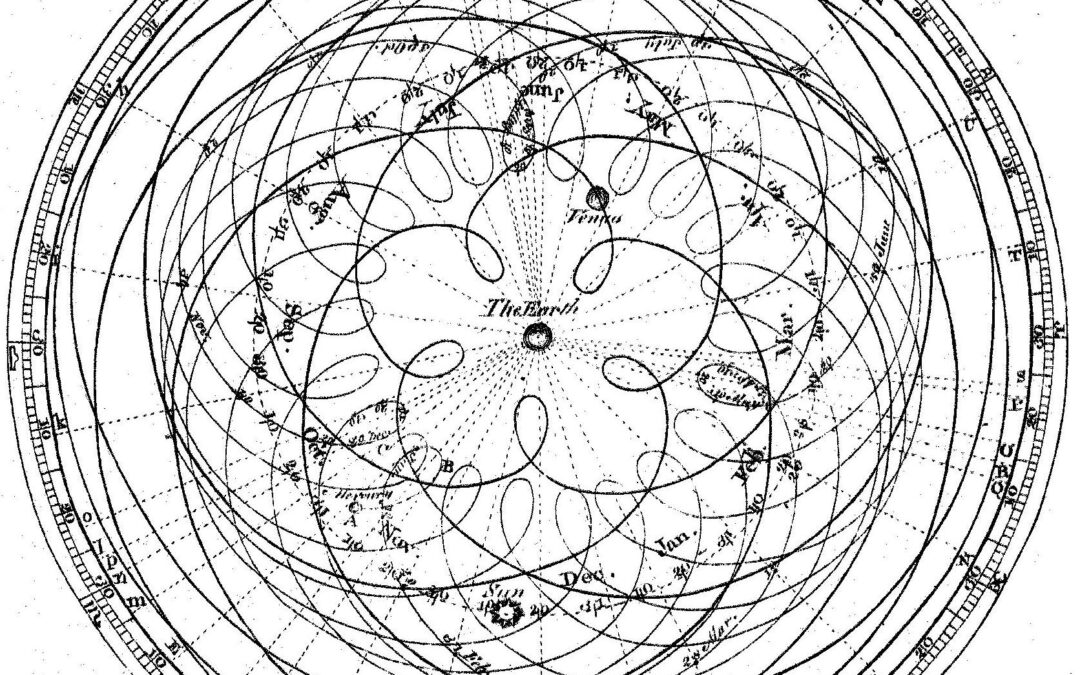

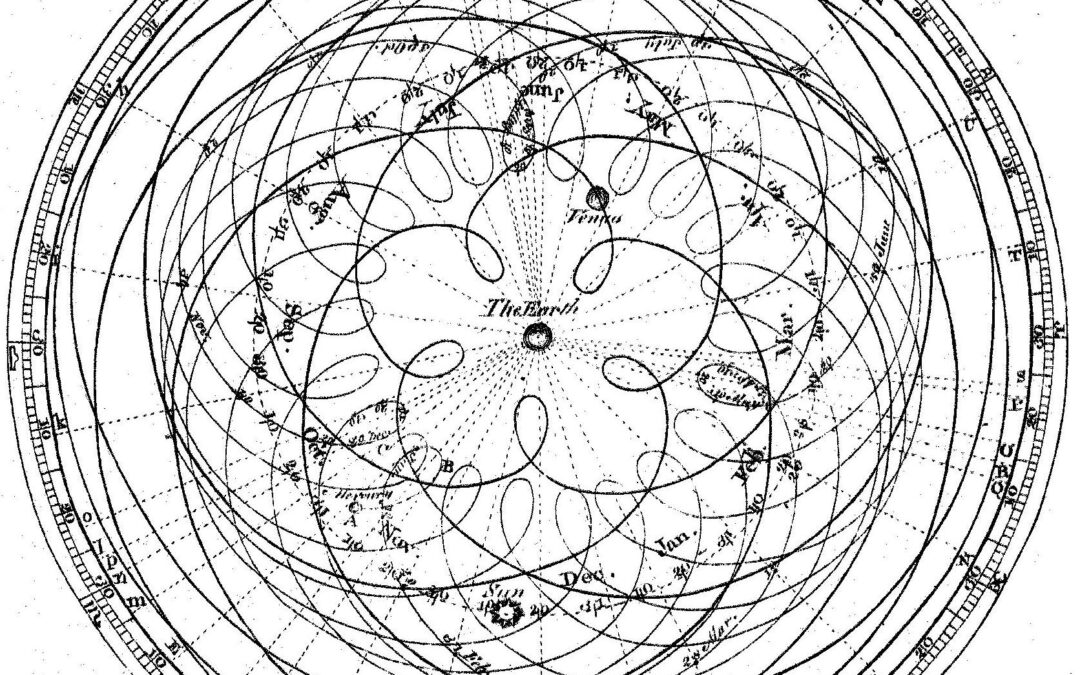

This story about medieval astronomy applies directly to investment strategies, market valuations, and portfolio construction today. It’s the same lesson –begin by questioning the very assumptions on which an entire system is built. There is also a very specific application of this model that is particularly current.

One of the most valuable lessons is to assume no knowledge and analyze closely every initial assumption. Nothing is so obvious that it can’t be questioned. Unexamined ideas and assumptions will eventually be useless. Any assumptions and any model used to explain and predict anything (whether it’s the movement of planets or financial markets) needs to go back to first principles and discard any assumptions, preconceived knowledge, or bias.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Economy, Finance, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

Economic predictions have always been highly variable and uncertain, and, for some reason, relied upon as if the future were a magical algorithm. Essentially, economists would make one fundamental mistake. They thought they were practicing a science. Data could be collected, inputted, and a predictive algorithm could be generated. Even Nobel Prize winners like Paul Samuelson believed that with enough data we could come to understand the economy and how it functioned.

This is nonsense. As Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have shown us, human behavior and irrationality, combined with unpredictability and randomness (thank you Naseem Taleb) make this even a questionable social science. Using existing analysis and algorithms to reliably forecast is a fool’s errand, essential for someone’s tenure, and maybe even a Nobel Prize, but doesn’t add much that is useful. Some of the more laughable Nobel Prizes have been given to people who determined that markets were efficient. They are not. Economies can be predicted with useful data input. They cannot. A couple of inputs about inflation and the unemployment rate, and we know how to manage an economy. We can’t. That last one is the Philip’s Curve – true for a limited time and then it goes spectacularly wrong – a lot like most risk and market prediction models.

One thing we can add is that most predictions seem too good to be true, and almost always are. The economy is not a perpetual motion machine, nor is it a credit card with no limit and no requirement to pay the balance. The current notion that “deficits don’t matter” seems patently silly and naïve to think that we can simply print money without any economic discipline to generate sustainable profitable businesses with the efficient use of capital.

“Money goes where it’s needed, but it stays where it is treated well.”

Walter Wriston (former CEO of Citicorp)

That means it has to generate a return and not be co-opted by governments and public policy, nor be flooded by capital with no economic discipline.

Deficits may be a reasonable way to jumpstart a sluggish economy, but they are not sustainable. Current thinking is that fiscal discipline, debt repayment, and the idea of a balanced budget are anachronistic and useless. It is dangerous to stress test this idea because the downside is potentially cataclysmic. Capital likes a free market, but we hardly have a free market with money today. Constant stimulus does not create economic discipline.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Currency, Digital Assets, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

“Distributed ledger technology and digital assets have the potential to dramatically disrupt global equity and debt markets.” (World Economic Forum, May 2021)

Distributed ledger technology (DLT), otherwise known as Blockchain technology, will radically simplify financial markets and, more importantly, fundamentally change the market’s infrastructure. Specifically, distributed ledger technology decentralizes critical data and enables an entirely new financial system where capital flows without the need for traditional intermediaries.

While there are challenges and numerous detractors, DLT is an irreversible disruptive force transforming capital markets and the global financial system.

Regulators (a potential obstacle) are increasingly comfortable with this technology. Distributed ledgers, decentralized finance, and Blockchain-based platforms are creating products and services evolving from exploration and experimentation to commercialization. DLT will be transformative to the world’s largest industry and represents an unprecedented opportunity. New digital platforms created by decentralized finance companies integrate securities and other digital assets comprehensively. The platforms enable market participants and intermediaries to issue, trade, settle, and provide custody services for digital assets, usually consisting of digitally native equity tokens (ICO’s).

These digital asset and financing platforms exist in parallel to existing market infrastructure and securities markets, in many cases offering an alternative digitized version of a standard asset class. Fundamentally, what is disruptive is that this new technology disintermediates all parties, creating effectiveness and efficiency in the transfer and recording of transactions that is unprecedented in legacy infrastructure

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Public Policy, Writing and Podcasts

Inequality is not an appropriate measure of economic performance or wealth creation.

Inequality is a relative and comparative statistic. It shows how wealth is distributed, which is not that meaningful, and certainly should not be the basis of economic policy. Essentially, inequality is a comparative metric and not an absolute one. That is, if everyone does better but a few people do much better, inequality increases, and this is seen as something bad even though everyone is better off. It is used to create misleading policies that focus on redistributing wealth that is created versus policy that should be focused on enabling greater and more distributed wealth creation – not wealth capture. Policy should focus on how to best create wealth for more people. The absolute degree of wealth creation is beside the point relative to other people. Creating opportunity for the most people is what matters.

As an example, overall wealth has increased over the last 30 years for every population group, but for the highest group, it has increased more substantially. But, why is that a problem? Instead, it is a natural and unavoidable outcome of the free market.

Here’s the analogy: if you want to hold a lottery, the prize has to be disproportionately large to have the most participants to raise the most capital. The simple goal is that net outflows (prizes) are smaller than the net inflows (contributions or purchased tickets). This is very similar to business opportunities and wealth creation.

As an economy, we want as many contributors to wealth creation – entrepreneurs and new businesses driving economic growth – as possible. The only way to do this is to enable market participants to have the greatest possible reward without restrictions. Most businesses will fail (much like most lottery tickets lose). But, because we have increased the number of willing participants, we also increase the opportunity to create the most wealth – the most businesses, jobs, and economic growth, as well as increasing the tax base from both businesses and individuals. So wealth creation, even if it is concentrated mostly in a handful of people, benefits the overall economy and society much more effectively than any attempt to limit that upside or redistribute it through politically popular but inefficient and demotivating policy.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

Risk is the permanent loss of capital.

It is not volatility, nor is it uncertainty. It is the realization of a loss. Therefore, risk is hard to understand because it is only clear with hindsight that a loss has occurred. Understanding how risk works can avoid this permanent loss by avoiding the mistakes that cause the permanent loss of capital.

Risk can also be used advantageously. Knowing that there is the prospect of loss, planning, and investment strategies that profit from these losses put you on the right side of the equation. Risk can be used to an investor’s advantage.

Essentially, anti-fragile (to coin Naseem Taleb’s term) strategies can benefit from volatility, uncertainty, and loss. Randomness permeates all markets, which means risk is always present. Knowing that, investment strategies need to be able to withstand unpredictable or unforeseen stresses. Not all risk factors can be known, or even if potential risks are identified, the magnitude and timing are unknown. What can be certain is that they will occur, and a portfolio that is “fragile” can be devastated

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

Prepare for more frequent and extreme volatility. New and powerful influences, ranging from social media and financial technology to algorithmic trading and esoteric valuation models, will increasingly upset market stability and bring unprecedented rewards and unpredictable disaster.

Predictable market conditions will be upset by sudden unpredictable movements.

Financial markets can be predicted reliably only when the world does not change. Even during periods of stability, judgment based on expectations and assumptions as much as hard facts and economic analysis, form the basis for buying and selling decisions. Market crashes and financial crises are a continuing and breathtaking reminder that markets are irrational and uncertain. Taken to an extreme, the combustible combination disrupts global markets and societies. New analytical tools and technologies appear to make worrying about unforeseen risks obsolete. But this naïve belief in technology’s ability to understand and predict catastrophic risk is a fundamental cause of that very catastrophe.

Stability is illusory because in an uncertain world, unforeseen changes can have seismic effects. The pandemic is only the latest example, but there are always greater risks inherent in markets than is acknowledged, and most investment strategies do not accurately reflect the risk that certain investments are assuming for a given return. Safety can be an illusion if the risks are not well understood, both systemic and undiversified.

As we have seen, oversight, regulation, or any sort of self-imposed moderation will continue to be ineffective or nonexistent, and always trail behind the most dangerous and detrimental market developments. Financial weapons of mass destruction continue to multiply and are now available via smart phone in everyone’s pocket. Expect more and greater turbulence.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

Clear and coherent markets, free from political agenda, bad compromises, and ineffective regulation is almost nonexistent. The consequences are usually pyrotechnic. It is not as if the world hadn’t provided ample warnings about the risks associated with irresponsible finance. History has centuries worth of such examples, but even looking at recent events over the last 25 years is illuminating.

In spite of Alan Greenspan acknowledging the “irrational exuberance” of the markets in 1996, stock market valuations continued to rise. The warning signs of unstable economies were believed to be localized and the broader markets decoupled from this turbulence. This was naïve thinking then and outright irresponsible now.

The idea that markets are uncertain, and consistent prediction is essentially impossible, is not new. John Maynard Keynes published a book on probability and uncertainty in 1921, with this concept of uncertain and irrational markets forming the basis of his general theory of financial markets. So, years before the stock market crash of 1929, and almost every 10 to 15 years afterward, the cycle of financial crashes and panics was predicted by a well-publicized thinker, and then, as is typical, ignored. The lesson is simple, and Keynes laid it out 100 years ago: markets seem rational but only during periods of stability. Markets are uncertain. Predictive models work most of the time, and that is their fundamental flaw. They will fail. Investment models that account for uncertainty and failure succeed in the long term.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

S&P 500 stock market values are experiencing the same volatility as the first half of 2020, the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (based on the 50 largest value movements as a percentage of the index’s total market value).

Heightened volatility has grown more common across the stock market even as major indexes are approaching record highs. The volatility is not limited to specific circumstances of craziness, such as GameStop (rising more than 2,000% and then cratering), or Viacom (losing more than half its value as Achegos imploded). Apple gained $265 billion in market value during only five trading sessions in January – more than the total worth of Coca-Cola. In March, NVIDIA and PayPal each lost over $50 billion in market value in just a couple of days.

These dramatic movements show that market volatility leads to big price movements in stocks, both up and down. There are a couple of factors combining to enhance this turbulence:

The popularity of the momentum trade (buying stocks that are rising quickly and dump the relative losers quickly).

Decreasing liquidity (fewer buyers and sellers for the other side of trades).

Both factors magnify the market’s moves in either direction.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

The Archegos implosion teaches the same lessons that apparently need to be taught over and over again. High leverage eventually brings margin calls. Margin calls equal disaster. Margin calls come when too much leverage is attached to securities linked to market volatility. All securities are linked to market volatility. There is no such thing as uncorrelated assets anymore. Investment strategies founded on the belief that the securities held are somehow immune from previously “uncorrelated” volatility are anachronistic. Combine these investments with substantial leverage intended to enhance returns, and this strategy ends in disaster. If it’s zero eventually, great quarterly performance is meaningless. It’s risk-adjusted return, idiot. Diligence matters. Questioning assumptions and decisions constantly are the table stakes for any investor. The too clever, overleveraged, overconfident manager believes work is done before an investment decision. That’s the beginning, not the end, and a failure to be diligent in a market with many more influences, uncertainties, and factors impacting a portfolio ends, well, the way Archegos ended. Watching carefully and acting quickly, getting out of suddenly unattractive positions, and revising thinking is almost as good as a good investment choice in the first place. Building a portfolio the way Archegos did is not investing. It’s gambling. The most important lesson is to know the difference.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Investment Principles, Technology, Writing and Podcasts

Fundamental drivers for pricing valuations in public markets have changed. Now, there is a new interaction among factors unseen just recently. Advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence have had a profound impact on the tools available and analysis presented to even the most amateurish investor. Social media, such as Reddit, Twitter, and other platforms, have allowed access to information and influence from media “stars” driving demand in an almost herd-like mentality driving up prices, and causing extreme volatility. Finally, technology has enabled a trading floor to be in everyone’s pocket. That same trading floor allows access to any information on anything from anywhere, and communication with anyone or, via social media, receive communication and information (regardless of how dubious) from anyone about any security or investment strategy.

These factors will cause unprecedented market volatility, along with extreme price movements for well-known (or perhaps more accurately, well-publicized) companies and their securities. While the supply of securities remains somewhat constant, demand for those securities is increasing (sometimes exponentially) because many more investors are now chasing those same securities.

The price of anything cannot escape supply and demand dynamics. Recent IPO activity is an attempt to meet growing demand (and raise capital at attractive prices). The new supply from IPO’s, secondary stock issuances, and most recently and monumentally, SPAC offerings, still do not provide enough supply to quench a growing and overwhelming demand. The valuations, especially those given to the SPAC’s, are entering stratospheric levels that could hardly be justified under normal market conditions. While there is plenty of capital, most assets seem fully priced with an under-estimation of risk. There are alternative investments where higher returns without the same commensurate increase in risk are available. Some return is simply mispricing of securities through lack of attention (those starved from social media can create meaningful opportunities for those savvy enough to look for them) or liquidity.

Successful investors are the ones who understand adding return without corresponding risk is the most critical component of successful investing, especially given the new equation for valuation:

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

When Everything is Going Great, It Probably Isn’t.

Things can only get better from here… said the turkey the day before Thanksgiving. It’s challenging to know when it’s too late because things go badly gradually, then suddenly.

It might be time to start worrying about tech-stock valuations. Usually, all it takes is a few overly ebullient stock analysts to set off an alarm. When unreasonableness takes over (remember all those analysts’ reports from March 2000? The NASDAQ could only go up and all those internet funds were going to double again in 2001?). In March 2000, the bellwether for this nonsense was Henry Blodget’s recommendation of Amazon with a target price of $400.00 by March 2001 (at the time Amazon was trading for about $60.00 a share). Instead of being $400.00 in March 2001, Amazon’s price was $5.97 per share.

Long Term Value Means Long Term

Of course, Amazon has created an amazing business model and is fundamentally rewriting technology services and customer logistics. Trading at almost 100 times earnings the market believes there is much more growth and profitability to come. Really? Regardless of your perspective about that, Amazon is an example of investments that are either “don’t bother it’s ridiculous” or “never sell it’s ridiculous.”

The market may stay permanently irrational about companies like Amazon, or Amazon may catch up to the market’s irrationality. What should an investor do? The answer is simple – don’t play. By that I mean you either buy the stock and ride the tiger (which means you can never get off – or sell) or stay out of the jungle completely – don’t ever buy. Half measures rarely have good outcomes.

Amazon is exemplary. This tiger has rallied substantially since those woeful days in March 2001 to close above $3,200 per share in February 2021. So, even if you listened to the absurdity belched out in March 2000, and on paper, had substantial losses from your Amazon investment for several years, if you held on, you are brilliant and rich (more like lucky; but it’s smarter to be lucky than lucky to be smart). Don’t listen to the analysts and don’t get off.