by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Currency, Economy, Public Policy, Writing and Podcasts

Central bank independence and fiscal responsibility matter, even though the Western world is acting as if these rules no longer apply. Well, perhaps. But the world has given us three examples where the consequences are extreme when these basic foundations of economic policy are ignored or violated. Ultimately, if markets lose confidence in a central bank’s independence and thoughtfulness (yes, thinking really matters), or a sovereign government’s fiscal responsibility (where thoughtfulness is never taken for granted), inflation expectations will undermine an economy and make recovery almost hopeless.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Writing and Podcasts

Failures are essential for success. The NASA flight director, Gene Kranz, who is famous for the Apollo 13 quote, “Failure is not an option” has been misunderstood. Mr. Kranz did not mean “don’t fail.” He meant was that there will be a solution, think boldly and courageously because, while the solution may not be obvious to you now, you will find it eventually.

Accepting failures is not accepting failure.

Failures – trial and error, unforeseen roadblocks, creative thinking, visions, and revisions that a minute will reverse – lead to insight, innovation, creativity, and unforeseen breakthroughs. That’s success.

Failure is when you stop.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Uncategorized

[iframe style=”border:none” src=”//html5-player.libsyn.com/embed/episode/id/20872907/height/100/width//thumbnail/yes/render-playlist/no/theme/custom/tdest_id/2730845/custom-color/3a8da9″ height=”100″ width=”100%”...

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Currency, Digital Assets, Investments, Technology, Writing and Podcasts

Decentralized finance (DeFi) can disrupt global finance – but only if Defi systems and central governments cooperate. Yes, sworn enemies cooperating for the greater good.

While each seems to be the sworn enemy of the other, ultimately, a cooperative relationship between decentralized and efficient (versus anachronistic and cumbersome) financial infrastructure and government central banks with stable currencies is absolutely necessary.

Defi transactions, to scale globally, require stable and predictable value. Government-issued currencies are the only reliable and foreseeable foundation. Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin were never currencies. They are a sideshow that will remain a speculative asset, and increasingly unimportant.

Cryptocurrencies represent an architectural shift in how financial infrastructure and technology interact, and therefore, it is disrupting how the financial industry works globally. It is neither a new kind of money system nor a danger to economic stability. It is more important than that.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Biotechnology, Book Chapter, Health Care, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

Investors have been swept up in the notion of “philanthropic capitalism” and have targeted life-sciences as an avenue that can fulfill this benefit to society. While laudable in concept, this is non-scientific surrealism. “Hoped-for” is not a reliable business model, and most of the unrealistic goals would not be sustainable even if achieved. Real science and innovation are more impactful and substantial and make life sciences even more.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

Distinguishing what’s happening in the market and the direction of important market metrics – the signal – from garbled, inconsistent, and mostly useless data – the noise – is extremely challenging today. Information is contradictory and transient making data and critical events more confusing and indistinguishable. Unusual circumstances brought about by the pandemic, subsequent supply chain interruptions, inconsistent production and demand, and unclear economic forecasts combined for almost unprecedented uncertainty and unpredictability.

Typically, near-term predictions are reasonable and reliable because we have immediately available and fairly accurate data making short-term predictions reasonably accurate. In other words, we can estimate what will happen because we have a good idea what just happened. But this is not the case today. Predictions based on the near-term past are more muddled now than ever. While we used to be able to say we can see a trend, whether that’s inflation, economic growth, or some other important metric, too much volatility, irrelevance, and lack of applicability (after all, who is going to project from a base that includes a pandemic impacting global supply chains and production?), we really can’t reasonably rely on any of that data to try to find a trend or connect the dots generating a near-term forecast with any meaningful depth of data and understanding

More intense volatility occurring more often will be characteristic of this market from now on. An investment strategy must withstand and profit from this. The only clear signal from the market is that there is far too much noise and not enough of a clear signal. Without clarity, determining an investment strategy is flying blind with no instruments.

Core holdings combined with an ability to withstand and profit from volatility and unpredictability are essential for investors today.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Book Chapter, Investment Principles, Investments, Writing and Podcasts

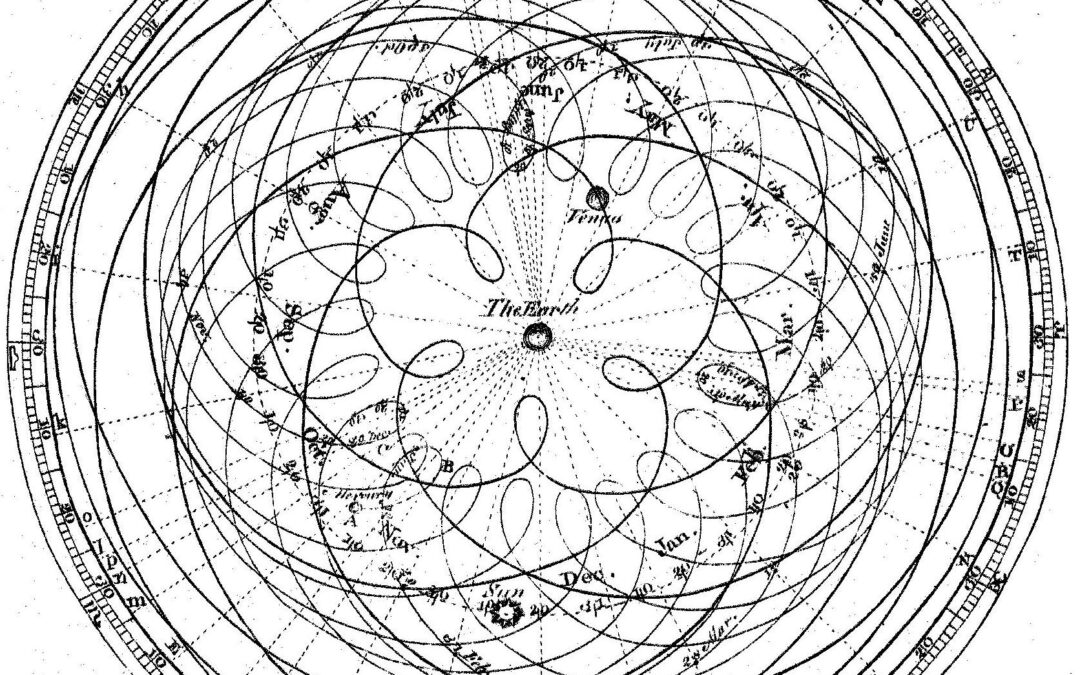

Assume nothing, new models and analytical tools, coupled with constant revision, questioning everything, reassessing, and re-analyzing, are essential to success in today’s markets. Often, and we are seeing that in today’s market, relying on bad assumptions, dogma, or prior belief can be disastrous.

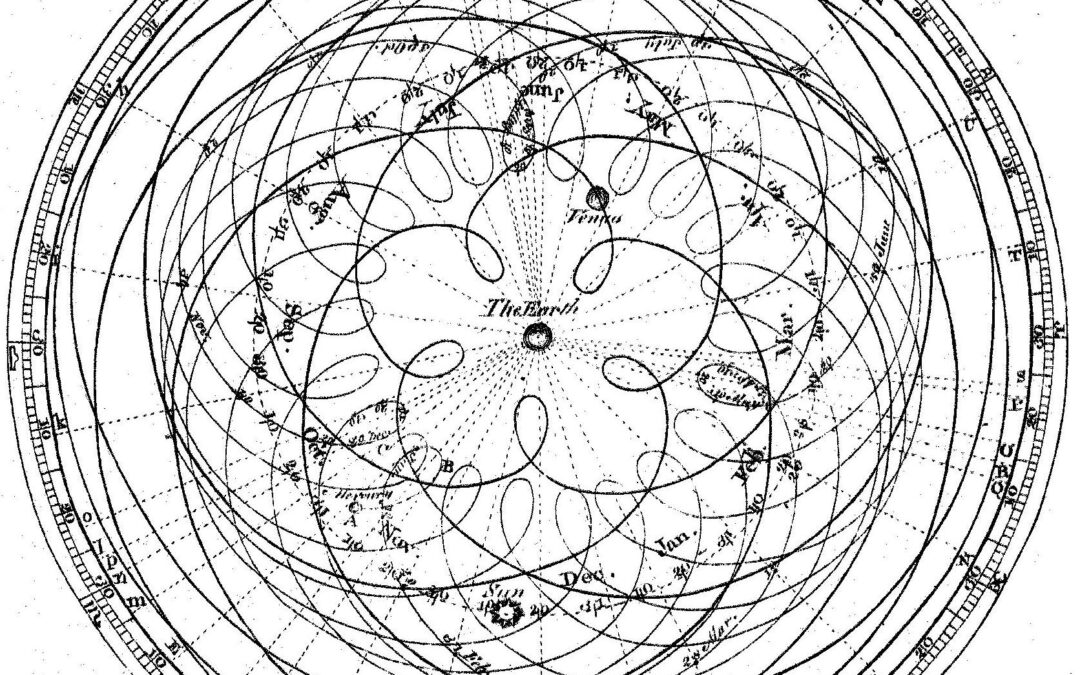

This story about medieval astronomy applies directly to investment strategies, market valuations, and portfolio construction today. It’s the same lesson –begin by questioning the very assumptions on which an entire system is built. There is also a very specific application of this model that is particularly current.

One of the most valuable lessons is to assume no knowledge and analyze closely every initial assumption. Nothing is so obvious that it can’t be questioned. Unexamined ideas and assumptions will eventually be useless. Any assumptions and any model used to explain and predict anything (whether it’s the movement of planets or financial markets) needs to go back to first principles and discard any assumptions, preconceived knowledge, or bias.

by Nicholas Mitsakos | Podcast, Uncategorized, Writing and Podcasts

Inflation fears, currency tremors, market jitters, and emotional vacillation causing joy and terror because all these outcomes seem equally likely. No realistic gauge is showing reliable directions for key metrics. Near-term data usually predicts the near-term future,...