This article was written by Nicholas Mitsakos : Chairman and CEO at Arcadia Capital Group.

The world’s business cycles are more moderate and lengthening.

Optimism is challenging when looking at the world economy. As the trade war between America and China continues, business confidence in America and elsewhere has been declining. Surveys suggest that, as trade growth slows, global manufacturing is shrinking for the first time in more than three years. Services have begun to follow manufacturing’s downward trend as domestic demand falters, even in economies with strong labor markets, such as Germany.

Long-term bond yields have been tumbling. Ten-year U.S. Treasuries have fallen from 3.25% to around 1.5%. Yields on 30-year German debt are negative. Low long-term rates signal that investors expect central banks to keep short-term rates low for a long time. Yet differences in yield between regular bonds and inflation-indexed bonds suggest that inflation will be even lower than the central banks’ targets – presumably, because their various economies will grow too weakly to generate much upward pressure on wages and prices (see “Discussion on Interest Rates and Investment Strategy”).

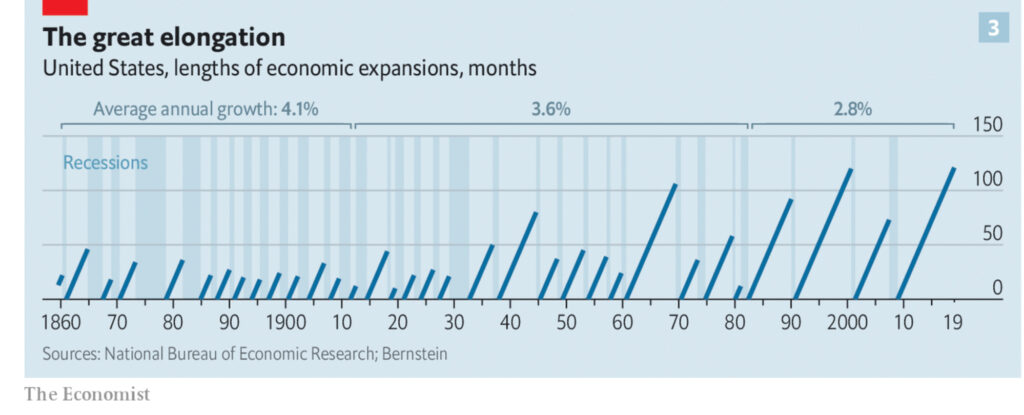

On top of all that, the current economic expansion is unprecedentedly long. America’s economy has matched the record for the longest unbroken period of rising GDP set in the 1990s. Europe has enjoyed 24 consecutive quarters of rising GDP. As these years of growth have continued, it increasingly likely to sense this growth will come to an end soon. Yet, it has not.

One clear lesson from the financial crisis of 2007-2009 was to refrain from celebrating long periods of growth. Before that crash, economists spoke of a “Great Moderation” that had tamed the boom and bust of the business cycle. Perhaps the high point of hubris came in 2003 when the economist Robert Lucas said that the “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved.” Of course, as with all acts of hubris, this was quickly reversed. The second half of the decade saw the most severe downturn in the world economy since the 1930s.

But the length of the current expansion suggests that the idea of a Great Moderation has some substance. Business cycles are caused by changes in total spending which outpace the ability of prices and wages to respond. Recessions happen when, faced with lower spending, firms sell less and shed workers, leading spending to fall further, rather than adjust prices and wages to balance supply and demand. The Great Moderation was marked by changes in the economy that made spending less volatile, and by a greater willingness on the part of central banks to promptly increase demand when things looked dicey. A financial crash could still end an expansion, as seen in 2007 to 2009. But over the long term, stretches of economic growth in America have got longer and longer (see chart below from The Economist).

Thus, this expansion’s remarkable longevity shows that none of the things which usually bring expansions to an end—busts in industry and investment, mistakes by central banks, and financial crises—has yet shown up. Why not? Is their arrival merely delayed, or becoming genuinely unlikely?

Manufacturing versus IP and services investment – countercyclical and complicated

First, take downturns in manufacturing and the magnitude of manufacturing inventories. In the days when companies planned production months in advance, a modest drop in demand often led manufacturers to cut production abruptly and run down inventories, deepening the downturn.

This factor now seems genuinely less important today. Better supply-chain management has reduced the size and significance of inventories; manufacturing has been shrinking both as a share of rich-world economies and of the world economy. As the current situation demonstrates, this makes it easier for the rest of an economy to keep going when factories slow down. Manufacturing has dropped in the face of the trade war, but, overall, the economy has held up. This is due not only to better supply chain management and decreasing importance of manufacturing overall but to the service industry’s increasing importance leveling out the economy. The same pattern was seen in 2015 when a slowdown in the Chinese economy led to a manufacturing slump. The overall economy continued to grow.

Some of the shift from manufacturing to services may be an illusion. Services have replaced goods in parts of the supply chain where equipment is provided on demand rather than purchased. At the same time, some firms that appear to produce goods increasingly concentrate on design, software engineering and marketing, with their actual production outsourced. Such firms may not play the same role in the business cycle that manufacturers did.

This blurring of manufacturing and services has been accompanied by changes in investment. America’s private non-residential investment is, at about 14% of GDP, in line with its long-term average. But less money is being put into structures and equipment, more into intellectual property. In America IP now accounts for about one-third of non-residential investment, up from a fifth in the 1980s (source: The Economist Intelligence Unit); this year private-sector IP investment may well surpass $1 trillion. In Japan IP accounts for nearly a quarter of investment, up from an eighth in the mid-1990s. In the EU it has gone from a seventh to a fifth.

Recently, this trend has been reinforced by another: investment is increasingly dominated by big technology firms, which are spending lavishly both on research and physical infrastructure. In the past year American technology firms in the S&P 500 made investments of $318 billion, including research and development spending. That was roughly one-third of investment by firms in the index. Just ten of them were responsible for investments of almost $220 billion; five years ago, the figure was half that. A lot of this is investment in cloud-computing infrastructure, which has displaced in-house computing investment by other firms.

In general, the rate of investment in IP tends to be more stable than that of investment in plant and property. When low oil prices led American shale-oil producers to reduce investment spending in 2015-2016, business investment fell by 10%, which in the past would have probably triggered a recession. But investment in IP continued, and although GDP growth slowed, it did not stop. This is an example showing that physical investment simply no longer carries the economic significance it used to.

Eventually, the wolf comes

Whether or not that is the case, it would be wrong to think that IP investment can rely on no matter what. When the dot-com boom of the late-1990s went bust, IP investment was one of the first things to fall, and it ended up dropping almost as much as investment in machinery and other hard assets. With tech companies increasingly dominating investment, it is worth worrying about what could now lead to a similar drop. One possibility might be a drop in the online advertising market, on which some of the biggest tech firms are highly reliant. Advertising has, in the past, been closely coupled to the business cycle.

It would also be wrong to think that the world weathered a potential recession in 2015-2016 purely because of changes in the investment landscape. The effects of a flood of central bank stimulus to credit expansion in China and a change of tack by the Fed were critically important.

The swift action by the Fed was particularly telling. Central banks’ tendency during expansions has long been to continue raising rates even after bad news strikes, cutting them only when it is too late to avoid recession. Before each of the last three American downturns the Fed continued to raise rates even as bond markets priced in cuts. In 2008, with the world economy collapsing, the ECB raised rates on ill-founded fears about inflation. It repeated the mistake in the recovery in 2011, contributing to Europe’s “double-dip”.

But since then there has been no such major monetary policy error in the rich world. Faced with the economy’s current weakness, the ECB has postponed interest-rate rises until mid-2020 and is providing more cheap funding for banks. It will probably loosen monetary policy again by the end of the year. In March the Fed postponed planned rate rises because of weakness in the economy and cut rates recently.

America’s monetary loosening allows central banks in emerging markets, many of which are also reeling from the trade slowdown, to follow suit. With America cutting rates they need not worry about lower rates pushing down the value of their currencies and threatening their capacity to service dollar-denominated debts. The Philippines, Malaysia, and India have already cut rates in 2019.

Inflation? What inflation?

Normally, as an expansion wears on, central banks face the fundamental trade-off between keeping rates low to aid growth and raising them to contain prices. But over the past decade that trade-off has essentially been off the table because inflationary pressure has stayed low. This has several causes:

- Labor markets are not as tight as people think; slack labor entering the workforce has been underestimated.

- Profits have a long way to fall before rising wages force firms to raise prices. Firms are generating significant excess cash, and therefore have a lot of wiggle room.

- Globalization and digitization of the economy are suppressing prices in ways that are not yet fully understood, but their impact is clearly on display.

In America core inflation, which excludes energy and food prices, is just 1.6%; in the euro zone, it is 1.1%. Anticipated inflation for next year is still only 1.7% in the United States and 0.9% in the euro zone.

Central banks do not seem to be worried about inflation but are focused on stimulus and economic growth. Rich-world central banks will have very little ability to materially impact an economy if it has gone into recession. Only the Fed could respond to a recession with significant cuts in short-term rates without moving into the uncertain and contested realm of negative rates. The question of how much damage negative interest rates do to banks is under increasing scrutiny in Europe and Japan (please see “Discussion on Interest Rates and Investment Strategy”).

In the face of a significant shock, the Fed and other central banks could restart quantitative easing (QE), the purchase of bonds with newly created money. But QE is supposed to work primarily by lowering longer-term rates. As these are already low, QE might not be that effective, and there is a limit on how much of it can be undertaken. In Europe the ECB faces a legal limit on the share of any given government’s bonds it can buy. It has set this limit at 33%. In the case of Germany, it is already at 29%. If the ECB were to restart QE (as expected) that limit would have to be raised. But it can only raise it so far.

A limit to maneuverability puts a premium on central bankers’ judgment; an error like that of the ECB in 2011 could have dire consequences. Current central bankers have shown excellent judgment, but there is turnover in critical positions imminent. Christine Lagarde will take over the ECB from Mario Draghi in November; Mark Carney leaves the Bank of England in January; and Jerome Powell, the Fed’s chair, may be replaced after the 2020 election. These are unknown devils.

I’m the finance industry, and I’m here to help

The prospect for a financial crisis may seem remote, but manias and crashes are far too common to dismiss. During the Great Moderation, the financial sector grew in significance. The enhanced role of an inherently volatile sector may offset the stability gained from the shift from manufacturing to services. The size of the financial sector certainly served to make the crash of 2007-2009 particularly bad.

In America, finance now makes up the same proportion of the economy as it did in 2007. Happily, there is no evidence of a speculative bubble on a par with that in housing back then. It is true that the debt of non-financial businesses is at an all-time high – 74% of GDP – and that some of this debt has been chopped up and repackaged into securities that are winding up in odd places, such as the balance-sheets of Japanese banks (a frightening bit of déjà vu). But the value of assets attached to this debt are not as uncertain as those prior to the financial crisis. In large part the boom simply reflects companies taking advantage of the long period of low interest rates in order to benefit their shareholders. Since 2012 non-financial corporations have used a combination of stock buybacks and takeovers to retire roughly the same amount of equity as that which they have raised in new debt.

And the present value is …

Low interest rates also go a long way to explaining today’s high asset prices. Asset prices reflect the value of future cash flow. In a low-interest-rate world, cash flow is more valuable than in a high-interest-rate world. It may look disturbing that America’s cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio has spent most of the past two years above 30x, a level last seen during the dotcom boom. But the future income those stocks represent really should, in principle, be more valuable now. Higher interest rates would impact these valuations dramatically, but higher rates also seem off the table for now. However, while asset prices should be higher on a present value basis, how much higher, and do current levels make sense? These current valuation levels may not be sustainable, especially for high-growth equities on whose valuation above-market growth rates are based. Interest rates may be low, but global growth is slowing, as well.

Low rates produce instability, not moderation…right?

Analysis by the Bank for International Settlements shows that since the 1980s the financial cycle, in which credit growth fuels a subsequent bust, has kept its length at about 15-20 years. In this model, America is not yet in the boom part of the cycle. America’s private sector, which includes households and firms, continues to be a net saver, in contrast to the late 1990s and late 2000s (source: Goldman Sachs). Its household-debt-to-GDP ratio continues to fall. It is rising household debt that economists have most convincingly linked to finance-sector-driven downturns, particularly when it is accompanied by a consumption boom. America and Europe had household debt booms in the 2000s; neither does today. The most significant run-up in household debt in the current cycle has taken place in China.

It appears the world economy is not at any sort of precipice, and there is room for continued growth, albeit moderate in nature. There are some risks, and it is hardly a sure thing.

The world economy’s unprecedented expansion hardly looks healthy; the trade war is negatively impacting investor confidence, and therefore market valuations. Central banks may not have the ability to create enough stimulus to offset this impact. Some valuations in the market seem unreasonable, given current global growth rates and future economic activity. But it remains likely that the world economy continues to grow moderately for some time.

It looks like the world really has made a change for the moderate. Economic cycles have not been defeated. There will be a downturn, overvalued equities will be corrected, and the less credit-worthy side of the credit markets will probably have an unfavorable resolution. But a financial crisis or dramatic downward movement seems very unlikely. A Great Moderation will continue.